Tag Archives: place marketing

Place Marketing: Can cities be brands?

- Sunday, 08 December 2019 11:28

- Written by Julian Stubbs

- 0 Comments

Meet the city stylists: A new breed of communicators shaping today’s place brands

- Tuesday, 15 May 2018 07:28

- Written by Julian Stubbs

- 0 Comments

A new breed of ‘city stylists’ and ‘cool coordinators’ are shaping perceptions.

A few years ago, when global urbanisation passed the tipping point of 50%, a new era was heralded: for the first time in the history of the planet, more humans were living in urban areas than in the rural environment. Cities have always been key focal points for developing culture, trade and politics as wealth, prosperity and communications propel us ever-forwards through history.“Like a piece of architecture, the city is a construction in space, but one of vast scale, a thing perceived only in the course of long spans of time.” Kevin Lynch, The Image of The City, 1960.Cities are complex organisms that shape-shift across history, sometimes influencing, or being influenced by, the fate of the mother state. Cities are dynamic environments, constantly in a state of flux, renewal, growth, expansion, and with numerous stakeholders, all with a vested interest in how the city functions and also how it is perceived at local, and global levels. Today, perhaps more than ever, cities are competing with one another. In the age of the digital nomad, where borders are soft, and employment is location-independent, cities are competing to attract their future citizens and to retain top incumbents. Cities have become brands, many positioning themselves as post-industrial creative hubs intent on seducing the mobile and fickle creative classes. As economies depend more and more on intellectual property, these city brands have had to up their game to woo potential citizens. Architecture has always been one of the key tools in city branding and provided a boon for so-called ‘starchitects’ as each city ticks-off their ‘must-have’ lists of Hadids, Fosters, Pianos, Koolhaas’s and Liebeskinds.

“Architecture is central to this urban rebranding, the skin on a town or city’s face.” Tom Dyckhoff, The Age of Spectacle, 2017.By attracting human capital in the form of intellectuals and artists, thinkers and makers, cities can become hotbeds of innovation, generating creative capital that in turn stimulates further development and economic growth. Attraction, thus, is a key aspect in enticing new burgers to settle down and set-up shop. A strong city brand can go some of the way in attracting interest. However, it is the ‘content’, the way in which a city can fulfil its promise, that is the ultimate litmus test. Hype can grab attention, but if there is little to substantiate the claim, or a lack of underpinning, then attention will be cast elsewhere and one only has to look at the history of utopian communities, such as Robert Owens’ New Harmony, in Indiana, USA, for evidence of how high ideals and promises vs actuality aren’t always guaranteed to produce a successful outcome. So, this begs the question: who owns the image of the city?

“Not only is the city an object which is perceived (and perhaps enjoyed) by millions of people of widely diverse class and character, but it is the product of many builders who are constantly modifying the structure for reasons of their own. While it may be stable in general outlines for some time, it is ever changing in detail. Only partial control can be exercised over its growth and form. There is no final result, only a continuous succession of phases. No wonder, then, that the art of shaping cities for sensuous enjoyment is an act quite separate from architecture or music or literature. It may learn a great deal from these other arts, but it cannot imitate them.”(Lynch)Many municipalities will claim that they own the image of their city. However, in today’s online world, Googling images of a city will often deliver swathes of visitor-generated content that reflects how the city is perceived – not necessarily how the municipality wants to portray it. As with many brands – the true owners are often not the brand itself, but its consumers.

Cities are people, not concrete

In 2016, I attended a forum in Rotterdam, discussing precisely this topic. Google searches on the term ‘Rotterdam’ produced unending images of the city’s edgy architectural icons. However, the people, and the culture of the city were rarely portrayed. ‘Betonville’ – was my own personal name for this phenomenon and the city’s overt leveraging of edgy architecture – a term that was somewhat validated by a speaker from the municipality’s city marketing department, who stated: “it’s all very nice, but concrete has no soul, and we miss the balance of the human element in the portrayal of our city.” Consequently, a strategy was devised to populate the citybranding image bank – part of the marketing Toolkit – with manifold shots of people on the streets in an attempt to display the character and multi-ethnicity of the city, on a human scale.“Potentially, the city is in itself the powerful symbol of a complex society. If visually well set forth, it can also have strong expressive meaning.” (Lynch)

However, this is all still very much in the ‘self-promotion’ category, pressing the ‘send’ button and launching one’s desired vision into the ether. The narrative is much more convincing when an independent third-party shapes the perception and, in the past, this would have entailed press junkets, plying reporters with lavish food and accommodation and hoping that they would be favourable to the cause. Those days are long gone, however, partly due to the breakdown of conventional media giving rise to new breeds of independent journalists and writers.

However, this is all still very much in the ‘self-promotion’ category, pressing the ‘send’ button and launching one’s desired vision into the ether. The narrative is much more convincing when an independent third-party shapes the perception and, in the past, this would have entailed press junkets, plying reporters with lavish food and accommodation and hoping that they would be favourable to the cause. Those days are long gone, however, partly due to the breakdown of conventional media giving rise to new breeds of independent journalists and writers.

Bringing in the press

Furthermore, to corral this new breed of reporters, bloggers, vloggers and foodies, still requires a well-considered strategy and coordinated vision if the city in question is to be represented optimally. Rotterdam has been one of the most successful cities in creating a buzz around its ongoing development in recent years. Always the poorer, less glamourous relative of long-term show-stopper Amsterdam, Rotterdam has had to fight damn hard to emerge from the shadow of its northern neighbour – now a mere 25 minutes away by regular high-speed train from the stunning, new, swoopy Rotterdam Centraal Station. The city’s previous claim to fame was based around Europoort – the sprawling harbour area east of the city stretching some 40km to the North Sea coast. It was this 24-hour hard-working mega-port that distilled the rolled-up-sleeves and no-nonsense, down-to-earth spirit that the Rotterdammers effortlessly embrace and embody. That, and the resolution to rebuild the city after it was devastated by bombing raids during WWII. The official city slogan ‘Make it Happen’ is firmly in tune with that characteristic. Now, as the modern city centre seeks space to expand, the former dockyards and industrial wharves are being turned into innovation docks, maker spaces and places of industrial-spectacle-verging-on-art as personified by artist and innovator Daan Roosegaarde’s Dream Factory in the city’s upcoming Innovation District M4H.Telling the story of a place

Despite the huge challenge in re-tuning the city’s somewhat drab industrial image into something altogether more melodious, it can have escaped nobody’s attention that Rotterdam is sweeping away the title of ‘must-visit destination’ across a plethora of media, varying from CNN and Huffington Post, to Vogue and The Guardian, throwing some serious shadow on Amsterdam, it’s old, historic competitor. It seems like every day the city is popping up in different media – a report in Spanish on the BBC World website or films on German TV around resilience and sustainability in the harbour city. This success is largely attributable to the efforts Rotterdam Partners – a focussed and dynamic organisation driven to put the city on the map. Moreover, within Rotterdam Partners, it is International Press Officer, Kim Heinen, who is being lauded for a strategy that makes other cities and destinations sit up and take notice. She has been referred to as the ‘city stylist’ by local blog ‘Vers Beton’ (fresh concrete): a title that is entirely appropriate.

‘So why are you called UP THERE, EVERYWHERE?’

- Sunday, 06 November 2016 05:10

- Written by Julian Stubbs

- 0 Comments

Fast forward to June 2nd. It’s 38 degrees centigrade outside, but we are inside one of the world’s coolest, but hottest, sustainable developments

We’re now running a digital workshop at the Masdar Institute, Abu Dhabi, in the United Arab Emirates. Masdar is a university, a renewable energy developer, an investor and is building one of the world’s most sustainable cities. The company comprises four integrated business units complemented by a graduate-level research university. Pretty impressive, and the people we meet are impressive as well. At this workshop I’m accompanied by two amazing UP members based in Dubai, Zar and Asra. Both are smart, fun and highly professional. The clothes worn at this session are a mix of western casual to arabic, and it helps to make for a really exotic and interesting session. We have great discussions around digital, Inbound Marketing, developing content and emerging trends. During this workshop we break not for a fika but for prayers. Again, we get great input and interaction at the workshops, with the noise level rising during the breakout sessions as the attendees really get into it. It was something I’ll never forget. I just think how lucky I am to have experienced two such contrasting places in the space of just a couple of weeks. From Lapland to Abu Dhabi.

We have great discussions around digital, Inbound Marketing, developing content and emerging trends. During this workshop we break not for a fika but for prayers. Again, we get great input and interaction at the workshops, with the noise level rising during the breakout sessions as the attendees really get into it. It was something I’ll never forget. I just think how lucky I am to have experienced two such contrasting places in the space of just a couple of weeks. From Lapland to Abu Dhabi.

So why are we called UP THERE, EVERYWHERE? Simply because we are.

Julian Stubbs is Founder & CEO of UP THERE, EVERYWHERE, the Global Cloud Based agency. More here: http://www.upthereeverywhere.com/whats-up/ Learn more about Fika: (http://www.bbc.com/capital/story/20160112-in-sweden-you-have-to-stop-work-to-chatCardiff? Definitely not Lagom

- Sunday, 23 November 2014 08:34

- Written by Julian Stubbs

- 0 Comments

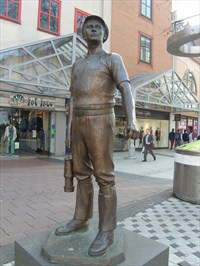

The Miner by local sculptor Robert Thomas, is a reminder of the sweat and blood that the city of Cardiff is built upon. It makes the point wonderfully well of how very different, and comparatively easy, our modern day life is.

Tim Williams CEO of The Committee for Sydney

Another key participant at the Capital City Vision Event, was Tim Williams – CEO of The Committee for Sydney. Tim, a proud Welshman, was formerly CEO of the Thames Gateway London Partnership where he made the Gateway in East London the key urban regeneration project for London and indeed the UK. Tim is recognised as one of the leading urban renewal thinkers and practitioners at work in the field, with an international reputation.

Tim’s brilliant speech focused on the future of cities. People are flocking to cities and most interestingly back to city centres. The dream of our parents and grand parents of living in suburbia is in full reverse. Thirty years ago inner cities had connotations of being dangerous, low quality slum districts but today more and more people want to live in the heart of cities. The easy access to amenities, connectivity and being able to conduct daily life in a simpler, lower cost way are some of the major drivers. These new urbanites offer many benefits to society as well, such as reduced carbon footprint as daily commutes are impacted and with people living in smaller city centre accommodation.

Bright Flight

These people are educated and seeking knowledge based jobs as well. This phenomenon is what the demographer William Frey has in mind when he says “A new image of urban America is in the making. What used to be white flight to the suburbs is turning into ‘bright flight’ to cities that have become magnets for aspiring young adults who see access to knowledge-based jobs, public transportation and a new city ambiance as an attraction.”

The point is to ensure you have some of what attracts ‘bright flight’: walkable urbanism.And it’s not just the young. Interestingly the baby boomers, who are now approaching retirement age, are seeking easier, lower cost, life styles with their larger homes in the suburbs now costing them more time and effort to maintain and heat. City centre living also reduces the need for cars. This means cities need efficient, good quality, public transportation systems as well as offering walkable urbanism.

Place Branding: The Drivers and Issues

My own speech in Cardiff focused on three aspects of developing a strong city brand. Firstly I looked at some of the drivers for city branding such as the attraction of tourists, inward investment as well as new tax paying residents. Place and city branding is one of the most complex marketing tasks that can be undertaken and has to involve a high degree of stakeholder contact. Identifying and involving the key stakeholders is central to any place branding strategy. Finally I looked at positioning, which goes to the very heart of place branding. Here I referenced my own work for the city of Stockholm and its positioning as The Capital of Scandinavia. The art of marketing is the art of branding. The art of branding is the art of positioning. What do you stand for and represent? I play a little game of asking people what one word they would use to describe a city. It’s one of the most challenging questions to answer for any brand and goes to the heart of positioning.

Place branding has grown enormously in the last ten years and as one place markets itself, very other place has to. Many of the disciplines of consumer marketing apply however to place branding. Like a traditional brand, places need to develop long term strategies. These should have a ten and twenty year perspective and not change with every political cycle. This means politicians need to be engaged early on and the strategy needs to have cross political party agreement to have a long term future. Stockholm’s has been in place now over ten years and has been through different political administrations successfully.

Building strong place brands can have a remarkable impact on cities. Just take the case of Barcelona. Today it is seen as one of the world’s most successful cities. However, it was all very different forty years ago. In the 1975 series Fawlty Towers Manuel, the hapless Spanish waiter who lived in fear of Mr Fawlty, was cast as coming from Barcelona. His home town was chosen with great care – as at that stage Barcelona was considered by many foreigners to be a run down, dirty, industrial black hole. It wasn’t until the death of Franco in 1975, that a new regional focus was put in place to get the city back on a path to regeneration. One of the key springboards in the strategy was the winning, and hugely successful staging of, the 1992 Olympic games, Barcelona is one of the few destinations to have run an Olympics at a profit. More than most places, the case of Barcelona proves that it is possible to turn around the fortunes of a city given the right strategy, a high degree of stakeholder involvement, focus and – most importantly – investment.

The Barcelona case was I felt relevant to my Cardiff presentation. Cardiff has been through a remarkable transformation since my youth. It’s already impressive. But the UK needs to embrace a more decentralised approach. London still dominates but turning the UK’s regional cities into new economic power houses would have tremendous benefits for the entire UK economy.

I was asked what one word I would use to describe Cardiff and spontaneously I replied passion. It’s a city with genuine passion and pride. You can feel it in meeting the local people and politicians. Lagom? Certainly not. Cardiff is a place that deserves to succeed and stand out. As the Capital city of Wales it also has a gravitas that most cities can’t match.

Cardiff has yet more potential to offer and I believe the best is yet to come. Granny Stubbs, my Welsh grandmother, would be proud.

—————————————————————– Watch an extract from the Capital City Vision speech here: